by guest blogger Fly News

In many ways, the 1920s and into the early 1930s can be described as in a snes the world’s “golden age” of aviation. Barely 20 years after the Wright brothers pioneered the first controlled flight of an airplane with a motor, and immediately following World War I, in which aviation made giant advances, peacetime unleashed a passion for making the world smaller thanks to airplanes. Aviators reached both poles; crossed the Atlantic Ocean; flew from Europe to Australia and South Africa; and even transversed the globe.

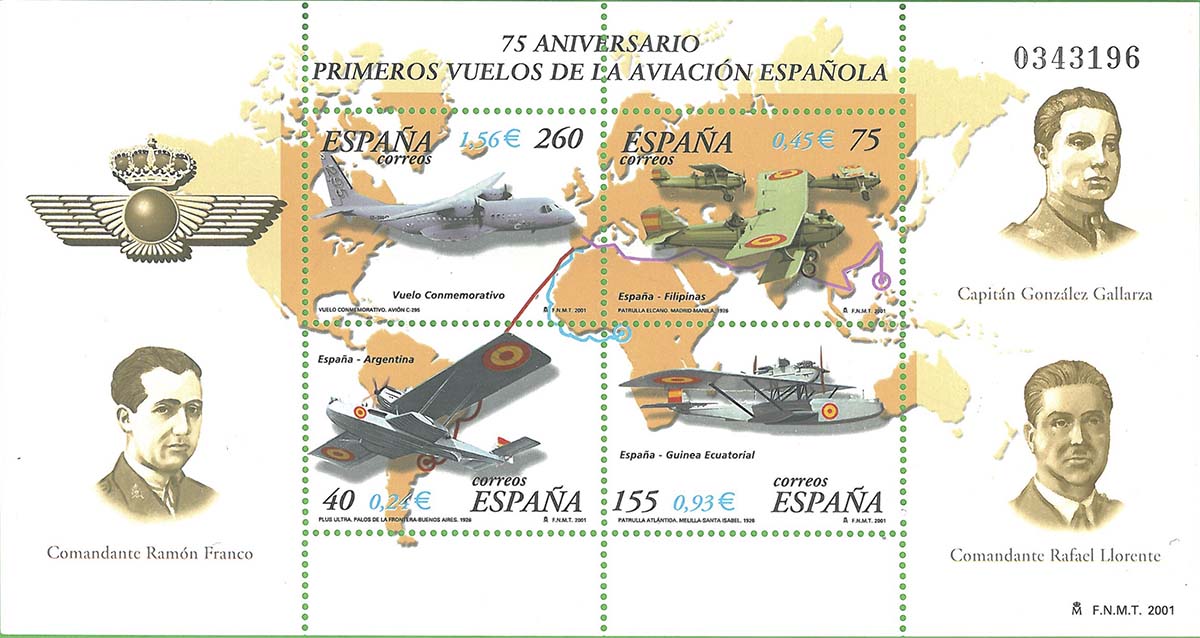

Spain, too, was part of this “aviation fever”, and proof of this was a series of daring and legendary expeditions by Spanish aviators. The first took place from 22 January to 10 February of 1926. the Plus Ultra (below), a German-made Dornier J Wall “flying boat” piloted by commander Ramón Franco and captain Julio Ruiz de Alda and accompanied by their navigator, lieutenant Juan Manuel Durán, and mechanic Pablo Rada.

This aircraft flew a total of 10,270 kilometres (6,381 miles) in 59 hours and 30 minutes between the Andalusia coastal town of Palos de la Frontera (in the province of Huelva) and Buenos Aires. The trip was broken down into seven stages, the longest single one being the transatlantic stretch – 2,305km (1,432 mi.) and 12 hours and 40 minutes – between Porto Praia in West Africa‘s Cape Verde islands and the Brazil‘s island of Fernando de Noronha (Rada didn’t participate on this one in order to lighten the plane’s weight, though he did rejoin the crew in South America for the rest of the expedition). And here’s an interesting fact: this team may not have been the first to cross the South Atlantic between Europe and the Americas, but it was the first to arrive in the same aircraft in which it departed. Today the original Plus Ultra is on display at the Museo de Transporte in Luján, Argentina, just under an hour north of Buenos Aires, and a replica can be seen at the Spanish Air Force‘s Museo Aeronáutica y Astronáutica in Madrid’s Cuatro Vientos neighbourhood (also home to the eponymous Cuatro Vientos Airport, at 111 years Spain’s oldest, and these days used by general aviation aircraft).

Next up, just several weeks later, was the Elcano Squad, which on 5 April 1926 took off from Cuatro Vientos to Manila in three CASA Breguet XIX aircraft (manufactured in Spain by a French company), the López de Legazpi with pilot Captain Joaquín Loriga Taboada and mechanic Eugenio Pérez; the Fernando de Magallanes with Captain Rafael Martínez Esteve and Pedro Mariano Calvo; and the Juan Sebastián Elcano with Eduardo González-Gallarza and Joaquín Arozamena. Flying in 17 stages, the expedition made it to the Philippines on 18 April, but it was only the first of those aircraft, manned by González-Gallarza and Loriga, which actually landed; the Magallanes went down in the desert of Jordan and the Elcano in Tien Pak, China. All six squad members also did ultimately return to Spain.

At the end of that year, the Patrulla Atlántida (Atlantic Patrol) flew from Melilla along the African coast to Spain’s colony Guinea Española (now Equatorial Guinea) and back, departing on 10 December and returning Christmas Day. It may not strike you as impressive as crossing the Atlantic or flying to East Asia, but in its day it was considered quite an achievement – such much so that in 1927 the patrol’s commander Rafael Llorente Solá was awarded International League of Aviators‘ second ever Harmon Trophy (the first having gone to Charles Lindbergh for his first solo Atlantic crossing). The patrol was composed of three Dornier J Wals: Llorente’s Valencia, in which he ws accompanied by mechanic Antonio Naranjo, radio/telegraph operator Lorenzo Navarro, and observer Captain Teodoro Vives; the Cataluña with pilot Captain Manuel Martínez, co-pilot Captain Antonio Llorente, photographer Captain Cipriano Grande Fernández Bazán, and mechanic Juan Quesada; and the Andalucía with pilot Captain Niceto Rubio, co-pilot Captain Ignacio Jiménez, mechanic Modesto Madariaga, and observer Captain Antonio Cañete.

The decade’s fourth great expedition took place in the spring of 1929, of a special, purpose-built CASA Breguet XIX (with an extra large fuel tank) known as the TR Gran Raid. Baptised the Jesús del Gran Poder (“Jesus of Great Power”) after a popular religious icon in its home city, Seville), it was christened by Spain’s queen Victoria Eugenia, and then on 24 March performed a two-day crossing from Seville to Bahía, Brazil – a distance of 6.550km (4,070 mi.). The pilot was Ignacio Jiménez (a co-pilot in the Atlantic Patrol three years earlier) and the mechanic Francisco Iglesias, and they intended to make it to Rio de Janeiro to break the existing world distance record, but ran out of fuel thanks to stronger than expected headwinds. From Bahía they continued on to Río, Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Santiago, Arica (in Chile‘s far north), Lima, Patía (in western Colombia), Colón (on Panama‘s Caribbean coast) and Managua, before heading across the Caribbean to Havana on 17 May, in the end having racked up 121 flight hours and some 22,000km (13,670 mi.). From there is was back to Spain where they were duly celebrated and fêted.

Pla

Pla

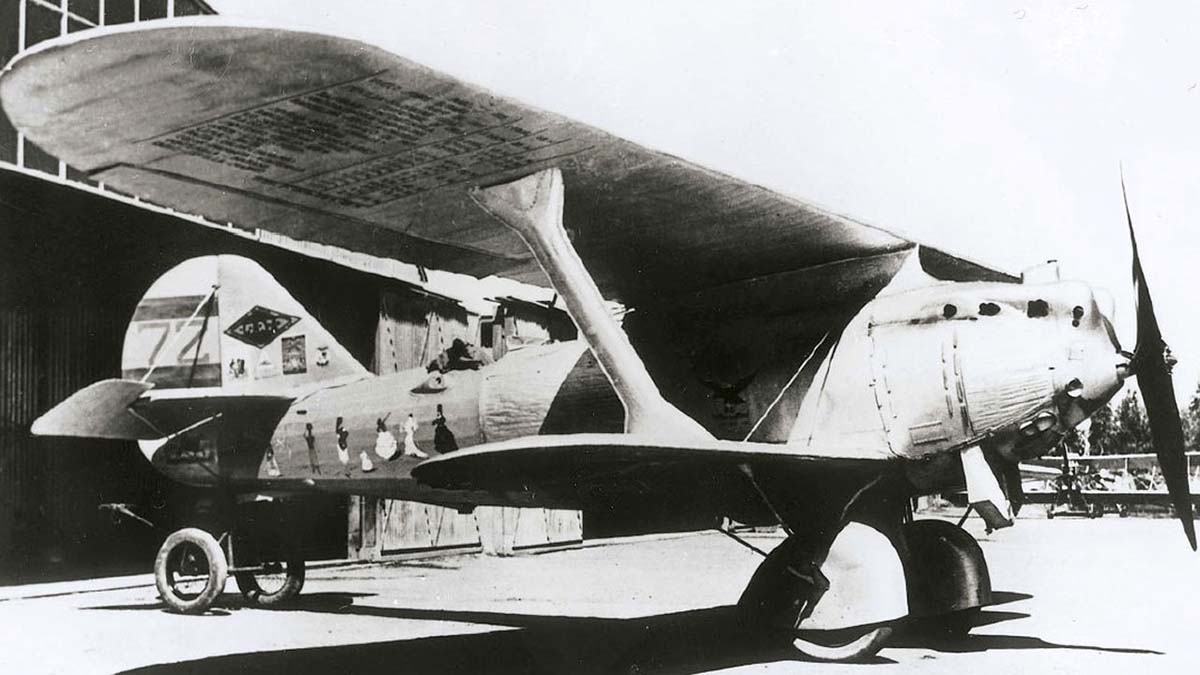

And finally, on 9 June 1933 the so-called Cuatro Vientos Flight, in a customised Breguet XIX GR Super-Bidón (referring to its also extra-large fuel tank), took off from Seville with Lieutenant Joaquín Collar Serra as pilot, accompanied by Captain Mariano Barberán, the distinguished aviator, war hero, and aviation instructor who conceived the project. The next day they arrived in Camagüey, Cuba, then the following day in Havana, having logged 39 hours and 55 minutes in the air, covering 7,895km (4,906 mi.). On 20 June the two proceeded on to the next leg of their journey, to Mexico City. Two hours and 50 minutes into the flight, their plane was spotted flying near the Mexican city of Villahermosa. But then – for reasons unknown but likely related to the terrible weather in the area – it disappeared without a trace, leaving behind perhaps the greatest unsolved mystery in Spanish aviation. A replica of their plane (above) is on display at the Cuatro Vientos museum today.