As I discussed in my last post, knowing some of the basics of how flying works and how controlled it is can be of significant help in alleviating fears and anxieties relating to flying. So this time I’m going to describe three amazing systems at work on every flight to help make your flight safe.

TCAS (Traffic Collision Avoidance System)

Pilots are comfortable only when they know they have everything under control and can keep it that way. At 18,000 feet (5,500 metres) and above, air traffic control (ATC) maintains separation between all airplanes. But small planes are allowed to fly below 18,000 feet without being under ATC control. These aircraft are hard to spot when flying toward the sun, or in hazy conditions. Feeling vulnerable, pilots wanted better control.

When it became clear a device could prevent mid-air collisions, the U.S. Airline Pilots Association began lobbying Congress to have it developed and installed on every airliner. As a result, all U.S. airliners were equipped with TCAS by December 1991, and other countries soon followed.

TCAS shows all nearby aircraft on a screen in the cockpit. Using a computer, this system determines whether any plane in the area could pose a collision threat. If the computer finds any possibility of collision, it alerts the pilots. If the threat shifts from possible to actual, the computer directs the pilots to climb or descend to a different altitude. As the pilots follow the TCAS instructions, they advise air traffic control of the altitude change needed to rule out the possibility of a collision.

From time to time, a “near miss” is reported in the news following an incident in which TCAS directed pilots to change altitude. Even when planes – following TCAS instructions – passed each other at a considerable distance, the media tends to characterise these incidents as a “near-miss”. Anxious fliers should understand that if reported accurately, incidents of this kind would not be “news”.

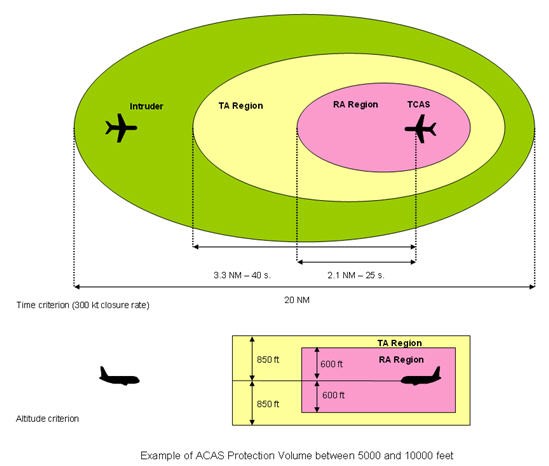

In the graphic at top, by the way, TA means Traffic Advisory. When another plane is approaching, if it moves into the advisory region, TCAS announces its presence by saying “traffic.” It is as if TCAS is telling you, “There is another plane in the area. I’m keeping an eye on it. I’ll let you know if you need to do anything.” The other plane will show up on your TCAS display in the cockpit. You can keep an eye on it on the display. As the other plane gets closer, you may be able to sight it visually.

If nothing more is heard from TCAS, it is satisfied that the other plane will pass by you with adequate separation. But, as the other plane approaches, the TCAS computer may calculate that more separation is needed. If so, the TCAS will issue a Resolution Advisory (RA), a call for action to increase the vertical separation. If your plane is flying level, the Resolution Advisory will instruct you to climb or to descend. When a RA is issued during climb, it may advise you to simply continue climbing. Or, depending upon the situation, it may instruct you to climb faster, or to stop climbing and level off. If you are descending, it may instruct you to continue descending, descend faster or to stop the descent. In any case, following the instructions ensures that the planes will pass by each other at different altitudes.

Instructions from the TCAS system override instructions given by air traffic control. When TCAS calls for action (provided it is not a false alarm) it means ATC has given bad instructions, or one or more of the planes has not followed ATC’s instructions. The pilots of each plane are expected to disregard ATC’s instructions, follow TCAS instructions, and to advise ATC what is being done.

GPSW (Global Positioning Systems Wing)

The second of these monitoring systems addresses one type of accident, termed Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT), which for years had continued to occur in spite of procedural safeguards aimed at preventing such accidents. “Controlled flight into terrain” means a perfectly functioning plane was flown unwittingly into the ground.

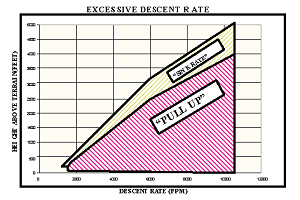

In 1969, Don Bateman, the chief avionics engineer for Honeywell, began developing a system to prevent CFIT. Bateman’s system used a radar signal from the plane to determine the distance between the plane and the ground. If the system saw the plane closing in on the ground, it automatically checked the position of the landing gear and flaps. If they were not in the proper position for landing, the system assumed the pilot was heading toward the ground – not intentionally for landing – but without realising it. This triggered flashing lights and a voice command – “pull up, pull up” – that continued until the pilot regained a safe altitude.

In 1969, Don Bateman, the chief avionics engineer for Honeywell, began developing a system to prevent CFIT. Bateman’s system used a radar signal from the plane to determine the distance between the plane and the ground. If the system saw the plane closing in on the ground, it automatically checked the position of the landing gear and flaps. If they were not in the proper position for landing, the system assumed the pilot was heading toward the ground – not intentionally for landing – but without realising it. This triggered flashing lights and a voice command – “pull up, pull up” – that continued until the pilot regained a safe altitude.

A later development, called the Enhanced Ground Proximity Warning System (EGPWS), bases its warnings not just on the radar signal between the plane and the ground but by tracking of the plane’s position and using an internal database to ensure adequate clearance above the terrain and manmade obstacles. This highly detailed database includes information on artificial objects 100 feet (30 metres) or greater in height. The worldwide airport database includes every runway of every airport an airliner could possibly use. This attention to detail is – to my thinking – good reason for passengers to feel safe when flying.

The EGPWS also monitors every landing to insure the plane is at the correct speed and in the proper position as it descends toward the runway. The EGPSW also has a build-in windshear warning system. Details on this amazing piece of safety equipment are available at this link on Honeywell’s website.

autoland

This is a fully automated way to navigate the plane down to the runway, land it, apply the brakes, and steer the plane as it slows down. This does two things: it makes landing possible in poor weather conditions, and it removes the possibility of pilot error when landing. Autoland was initially developed in Great Britain due to frequent local fog. Radio signals aligned with the runway guide the autopilot, both left-right and up-down as the plane descends for landing. The accuracy of autoland makes it possible to land in almost any weather conditions, provided the plane, the pilot, and the runway have proper certification.

Tom Bunn, L.C.S.W., is a retired airline captain and licensed therapist who has specialised in the treatment of fear of flying for over thirty years. He is the author the bestselling book on flight phobia, SOAR: The Breakthrough Treatment for Fear of Flying. His company, SOAR, Inc., founded in 1982, has helped more than 7,000 clients control fear, panic, and claustrophobia.

images | Eurocontrol, FAA