Stacey Wittig

Stacey Wittig

In the Roman Catholic world, today is the feast day of St. James the Greater, one of the apostles of Jesus Christ as well as the patron saint of Spain. In normal years it’s a red-letter day on this country’s cultural and tourism as well as religious calendar, marking the high point of two weeks of festivities in Galicia‘s capital Santiago de Compostela. These celebrations honour perhaps Spain’s most famous saint, whose remains are held by tradition to rest in a shrine in the city’s elaborate, largely 12th-century cathedral.

In this city’s UNESCO World Heritage old quarter and beyond, there are fireworks, as well as cultural and other events, all culminating in a high mass in the cathedral. In this year of coronavirus and COVID-19, of course, such mass gatherings will be scaled back or cancelled altogether. But the famed Camino de Santiago (Way of St. James), which basically runs from Paris and other spots in Europe down to northern Spain, then across to Santiago de Compostela (with a number of variations and side route – the original one is called the Northern Way or Primitive Way, and the best know is the the French Way), has been one of the world’s major religious major pilgrimages since the 9th century, and to this day it’s active all year round, popular not just with the faithful but also travellers eager to experience the myriad, extraordinary historic towns and cities as well as lovely landscapes along its routes.

In many of these places, visitors may spot these pilgrims with their backpacks and walking sticks. They’re a doughty brother- and sisterhood, and share a number of singular traditions and customs – some dating back centuries – as they spend weeks and even months walking the highways, byways, streets, and forest paths of Galicia as well as Navarre, Euskadi (the Basque Country), Cantabria, and Asturias. And so here are seven of the most notable (and please keep in mind that some may be affected at least this year by restrictions imposed by coronavirus prevention measures):

Lisa Morales Photography

Lisa Morales Photography

Carrying a Scallop Shell

“One of the Camino legends involves St. James’ divine intervention to save a bridegroom and his horse, who emerged from the sea covered in scallop shells”, says photographer Lisa Morales, who documents life along the Way. Another legend has it that the ship carrying the body of St. James to the Iberian Peninsula from Jerusalem sank, but the body was found on the beach protected by scallop shells. The shell is also imbued with a greater symbolism because of its form, with grooved lines leading from various points along the wide outer rim to a single meeting point at the base – echoing the trajectory of pilgrims from all over the world.

“In earlier days”, Morales notes, “the shell was carried on the return trip as a proof of completion of the journey”. These days commercially produced shells can be purchased at many shops along with Way, often emblazoned with the symbol of the 12th-century Order of Saint James. “One beautiful tradition is for pilgrims to be gifted with their shell even before setting out on their journey”, Morales adds, with friends gather for blessing ceremonies and presenting soon-to-be pilgrims with their shells. (Fun fact: as fans of French cuisine may know, the classic seafood dish coquilles St-Jacques is named after this scallop shell.)

Stacey Wittig

Stacey Wittig

Hugging the Saint

Some customs, such as pilgrims hugging the cathedral’s statue of St. James once they reach their destination, stem back hundreds of years. “Climbing up to embrace the saint, early pilgrims would remove their hats, place them on the head of the sculpture, and then perform many embraces, sometimes as many as 15 or more,” explains Anne Born, a Camino expert and author of the upcoming book If You Stand Here, a guide to the cathedral for pilgrims. “Visiting Italian diplomats in 1669 remarked that the practice was ridiculous, that the statue resembled a clown changing hats every few minutes. By 1700, the practice we know today was in place – just a hug and a prayer of thanks.”

Authorities banned another ancient practice after millions of grateful hands left deep, hand-shaped grooves on the cathedral’s main gateway, the Pórtico da Gloria. The ritual had pilgrims placing the fingers of their right hands into a carving of the Tree of Jesse on the portico’s central pillar. With fingers inserted into the hollow left by others who had gone before, pilgrims gave thanks for their successful pilgrimage or petitioned Santiago, who stands on the pillar. After so many touches, authorities feared the deepening imprint would compromise the structural integrity of the column, and consequently prohibited the tradition.

Bodegas Irache

Bodegas Irache

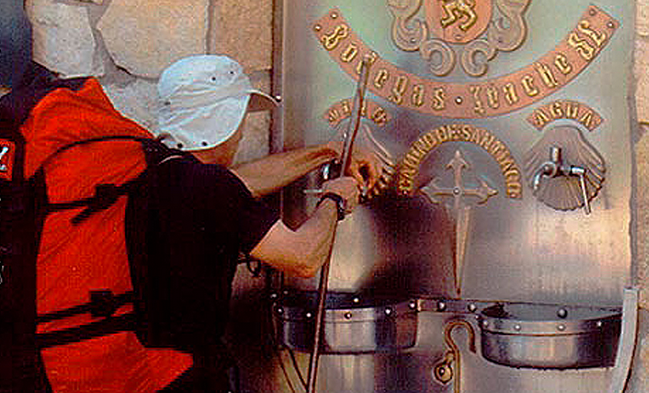

Hoisting a Cup of Red Wine

A contemporary tradition arose after the winemakers at Bodegas Irache, which adjoins Navarre’s 8th-century Monasterio de Irache, built a wine fountain to provide pilgrims with a free cup of red wine. Fortifying yourself with wine or water at the one-of-its-kind fountain near the hamlet of Ayegui is now a pilgrim ritual – and yes, an Instagrammable occasion.

jenniferStr

jenniferStr

Bringing a Stone & Leaving It behind

Pilgrims bring a stone from home to symbolise a prayer request or a sadness or burden they would like to leave behind at the the foot of the Cruz de Ferro (Iron Cross), mounted on a five-metre (16½-foot) wooden pole outside the Galician village of Foncebadon – which also happens to be the highest point along the Way’s most popular route, the Camino Francés (French Way). “I carried a heart-shaped stone from home in honor of my husband, who died two years earlier,” reveals Nancy Reas of Eastsound, in the USA‘s Washington State. “On my way to the Cruz, I decided I didn’t want to give it up. I kept my eyes on the trail and, of course, found another heart-shaped stone to leave—also several others for other people on my mind. My hands were full by the time I got there. And my heart also.”

Fresco Tours

Fresco Tours

Exchanging ‘Secret Handshakes’

OK, it’s not an actual “handshake”. But pilgrims do often offer each other a cheery and unique greeting, “buen Camino”, which means “good road” or “good way”. Another pilgrim salutation is “ultreia”, derived from Latin, which medieval pilgrims used as a word of encouragement. It translates as “beyond” or “on the far side of,” and tired walkers say it to cheer themselves and others on, to keep moving onward. And in these days of coronavirus, of course, both greetings are perfect “virtual” handshakes.

Joel Carillet

Joel Carillet

Attending Pilgrim Masses

The big league of Camino masses is of course the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela (above), but along the Way, local churches also hold masses specifically for pilgrims. Not all walkers attend the religious services, but those who do receive unexpected blessings. Tracy Pawelski, author of One Woman’s Camino, recounts, “after many months of going to mass in Spain, I realized that the services were spoken in a language that I didn’t understand. And yet I had understood.” Mysteries like this are common along the Camino de Santiago.

Stacey Wittig

Stacey Wittig

Stamp Collecting

Camino pilgrims carry a credential or pilgrim “passport” that allows them to stay at pilgrim accommodations along the Way. At each shelter, called a refugio or albergue, they then receive a stamp to prove they made it that far. Collecting sellos is a much-loved ritual, but beyond the tradition, pilgrims walking the final 100 kilometres (67 miles) must get two stamps per day, a requirement to receive a Compostela, a certificate of completion from the Pilgrim Office in Santiago.

Stacey Wittig is the author of three Camino books, including Spiritual and Walking Guide: León to Santiago. Her bylines have appeared at Forbes, the Telegraph and FWT magazine. Follow her blog UnstoppableStaceyTravel.com to uncover the spiritual side of travel.