That air travel is the safest form of transportation going is not mere happenstance but rather due to rigourous maintenance of equipment and exhaustive training of personnel.

Although in 2010 Iberia added a major maintenance hangar at Barcelona airport, since the 1970s the primary maintenance facilities have been headquartered adjacent to Barajas Airport in a suburban Madrid industrial zone called La Muñoza. This 220,000-square-metre (54-acre) is where aircraft engines constantly arrive for tuneups and repairs — whether after accumulating a standard number of flying hours or takeoffs/landings, or, much less commonly, due to malfunctions. Iberia’s own aircraft are brought directly in and their engines detached, while those of other airlines are trucked in from Barajas.

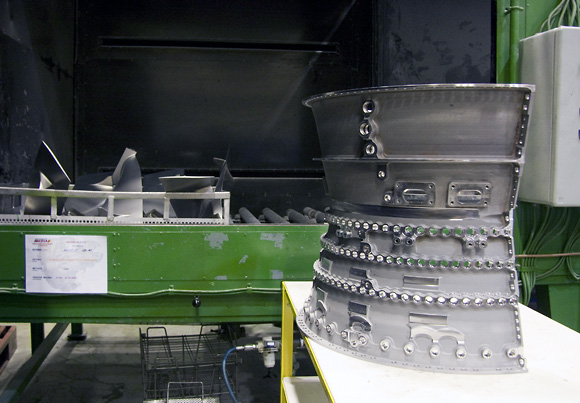

Once the aircraft is inside the maintenance hangar, first off the fairing is immediately removed in three primary sections: the nucleus, the ventilator, and the accessories. These sections are dismantled in turn by company mechanics, and all their component parts (except those which have reached the end of their useful lives), are temporarily stored in bins according to the materials of which they are composed. These bins are put through a huge washing machine which cleans each type of component according to its specific materials and characteristics. Except for its size and scale, it is, interestingly enough, not dissimilar to a dishwasher.

Once they’ve been cleaned, the components are carefully inspected to ensure that they are still in optimal working order. Depending on the materials of which they are made, inspection methods may include visual; ultrasound; X-ray; ultraviolet light; and immersion in fluorescent liquids that reveal the tiniest of cracks.

The components which pass this initial inspection are submitted to a second round of measurement by sophisticated equipment installed in a climate-controlled room, to ensure that they are not unduly affected by heat or cold, and their dimensions can be established to a precision of ten thousandths of a millimeter. If they pass this final inspection, they are finally declared ready to be re-installed in one of our aircraft engines.

Those pieces which do not pass any of the above inspections undergo screening to determine whether they can possibly be repaired. Any repair procedures undergone by any aircraft component must be one approved by the manufacturer.

One of the more spectacular repairs is plasma regeneration, in which layers of new material are ‘bombarded’ in plasma form onto the pieces. These pieces must then be rectified to eliminate any extra material and leave them at the exact size and shape required. For this, Iberia also use an advanced technique which allows the rectification of pieces that will go into the same engine. Another impressive technique is a robotic station for the treatment of turbine blades — those bladelike pieces we see when we look directly into an engine.

All of these procedures are exhaustively documented each step of the way, with each engine check generating thousands of computer records.

Once all the components have been screened, the engine is reassembled, with special care given to ensuring that they are all in balance, given that many of these are required to spin at a rate of thousands of times per minute. The reassembled engine is then submitted in its entirety to a final battery of tests in a facility adjacent to the engine shop; the engine is suspended from an adapter with the same hookups running from an aircraft wing – fuel lines, hydraulic circuits, control and signal lines, and so forth — and put in operation to verify that all parameters are correct with regard to vibrations, power output, temperature, and more.

Interestingly, testing in different parts of the world can yield different results in part because of differences that include altitude variations. It is a tribute to the work that is executed in Iberia’s facility at La Muñoza, that it is extremely rare that any engine that has passed through here be rejected by any test battery.

In fact, far from representing a cost for Iberia, thanks to its capacity for processing more than 200 engines per year of the models CFM56, RB211 and JT8D, this facility is actually a major source of revenue, due to the fact that up to 70 percent of the engines processed here belong to up to 100 or so other carriers, paying between $2 and $4 million each for this service.

Let’s wind up our visit to the Iberia engine shop with a stop at Hangar 6, the one with the big yellow arch. This structure, which contained Europe’s largest translucent space when it debuted in the 1990s , is where Iberia’s maintenance crews conduct operations which go beyond the normal everyday. As in the engine shop, aircraft of other carriers are serviced here in addition to Iberia’s.

These reviews and procedures can be minor maintenance (types A and C), or major maintenance (type D). During a type-A review, carried out after every 600 flight-hours, inspections are performed of the general systems, components, and aircraft interior and exterior structure to verify their integrity and that all equipment is functioning properly.

A type-C review, performed every 18 months, is a complete and exhaustive interior and exterior inspection of an aircraft’s structure and all its systems. Type-D reviews, which take approximately a month to perform, require the nearly complete dismantling of an aircraft in order to reach and check areas not normally accessible, such engine wing supports, landing gear, flight controls, and other aircraft systems.

As with the engine shop, all these maintenance procedures are impeccably documented–although it’s obviously unavoidable that an aircraft may occasionally need unexpected maintenance. Finally, once all reviews are completed, all engines and aircraft are submitted to flight tests before being returned to regular passenger service, as safety is the number-one priority.