Rio de Janeiro famously boasts one of the most spectacular natural settings of any major world city, a charismatic interplay of ocean with dramatic plunging hills (the most dramatic and reknowned, of course, being Sugarloaf and Corcovado). And though much of Rio has a prosperous enough air, there has always been much poverty here, too, and since the late 19th century, many of those dramatic hills also became home to sprawling, unofficial slums – originally built by decommissioned soldiers and freed slaves, and greatly enlarged in recent decades by peasants moving in from the country. Today these favelas number some 600, and are home to nearly 12 million.

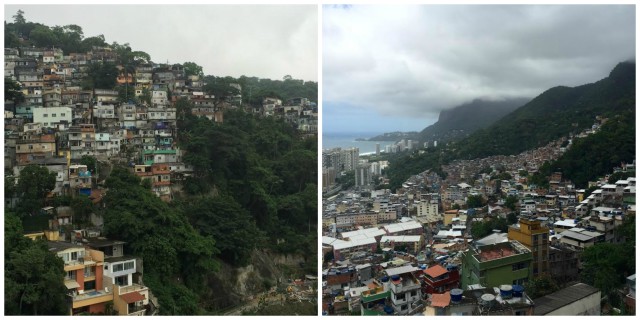

Recently, on my last visit to Rio, I stood on my balconey at the marvellous Sheraton Grand Rio Hotel & Resort – one of whose many singular attributes is that it’s right across from the Vidigal favela (top left), which rises above one of the city’s tonier neighbourhoods, São Conrado. Right before me, the jumble of blocky houses – cement-block grey mixed with every imaginable colour – zigging and zagging and cascading amid the greenery put me in mind of a complex Cubist painting come to life.

Interestingly, the Sheraton has never had a security problem from Vidigal. Yet as you can imagine, many of these communities have been difficult, rough-and-tumble, even out-and-out violent places for generations – both for locals and visitors. It’s an image and reality crystalised by the violent, searing 2002 film Cidade de Deus (City of God), about the eponymous favela way off the beaten tourist path, a 45-minute drive west of Copacabana.

In recent years, however, a mix of social programs, police/military “pacification”, and social evolution (now not just poor people but also sometimes middle class folks) have improved security conditions in many, to the point where visitors can freely wander some of them. And instead of being universally scorned and marginalised, “favela chic” has even become trendy in some quarters, especially pop music and art (not unlike so-called “ghetto chic” in the USA, actually). Over the past couple of decades, they’ve also been the settings for various movies, videos (most notably Michael Jackson’s 1996 “They Don’t Care About Us”, below, partly shot in Santa Marta favela) and especially video games.

Personally, I recommend anyone who wants to visit should do it on an organised tour, at least the first time. The maze of streets, lanes, and stairways up here can be confusing, and the guides know exactly where to go; take note of your locations, and you can always take a taxi back and explore on your own. On my first visit to Rio in 1999, I took a tour of the most-toured favela, Rocinha, and this last visit I decided to do it again. One of the city’s most respected tour operators, Jeep Tours runs a three-hour excursion for 124 reais (currently £23/€30/33USD) that gives you an excellent taste.

Since my last visit, things were looking a lot more developed, with more elaborate shops and businesses – and of course there was no WiFi back then! Clumps of wires are still strung along streets en masse, and most of the buildings still have a higgly-piggly, haphazard look. But you also get a sense of solidity, that this community is in it for the long haul. We glance into doorways as we pass to glimpse living spaces both humble and surprisingly fancy (we even entered one for a brief but enlightening Q&A with a woman and her teenage son). Down the street, we peeked in on a kindergarten class where bright youngsters in a brightly decorated classroom seemed happily engaged with a maths lesson. We also got to chat for a bit with barber Wilfredo, his hole-in-the-wall establishment emblazoned with photos of Che Guevara (below).

An extraordinary and sometimes moving experience indeed. And while of course most of the people you’ll be introduced to are hand-picked, they’re willing to frankly discuss anything, and there are plenty of opportunities for spontaneous experiences and encounters, as well.

Some have looked askance at favela tourism, saying it amounts to little more than “slumming” and “poverty voyeurism” by privileged foreigners. But I for one am convinced it’s an excellent opportunity for the privileged leave our bubbles, to be exposed to instead of insulated from the reality of economic and social inequality in this world. And furthermore, some of the profits from these tours do get to the residents, which can only be a good thing.

Best Iberia fares to Rio from the U.K., from Spain.

photos | DPA