Just a few days ago, Spain’s parliament approved a measure granting Spanish citizenship to Jews whose ancestors lived in Iberia until the tumultuous history of the day led to their exile. These Sephardim (from the Hebrew Sepharad or Sefarad, meaning Iberia) once numbered more than 200,000; contributed to economic, governmental, and especially cultural life; and included the entire population of some towns, such as Lucena in the Andalusia province of Córdoba. And to this day in many parts of the country, one can still experience their culture and architecture.

Córdoba

The eponymous provincial capital was one of the primary centres of Sephardic Jewry, and the place where it probably reached its apogee in the 7th through 15th centuries, thanks largely to a peaceful, prosperous co-existence with the Muslim then rulers of Al-Andalus; its spirit is epitomised by the 12th-century rabbi and philosopher Maimonides, one of the great figures of the Middle Ages.

More than five centuries after both Jews and Arabs left, both multiculturalism and even a certain whiff of mysticism still pervades the whitewashed cobblestone maze that is this city’s Judería, where visitors can learn about the city’s Jewish heritage at the Casa de Sefarad (aka the Casa de la Memoria, House of Memory), Tiberíades Square, and the Córdoba Synagogue, Andalusia’s only surviving Hebraic house of worship of this era.

Seville

In Andalusia’s largest city, Jewish culture flourished especially in the city-centre neighbourhoods of Santa Cruz and right alongside it, San Bartolomé, just metres away from the city’s majestic catedral. Seville’s Jewish quarter is one of Spain’s most ancient, and easily recognisable for its narrow, labyrinthine, sometimes sloping lanes – winding past plazas and historic buildings from quaint to sublime – all like a place where time has stopped. Calle Pimienta, Calle Mateos Gago, Callejón del Agua, along with San Bartolomé and Santa María la Blanca, synagogues turned into churches – all are key parts of this culturally fascinating route. Another is the Jewish cemetery, outside the walls of the old city, and the Centro de Interpretación de la Judería, an intepretive history that does a wonderful job laying out the medieval Sephardic experience.

Toledo

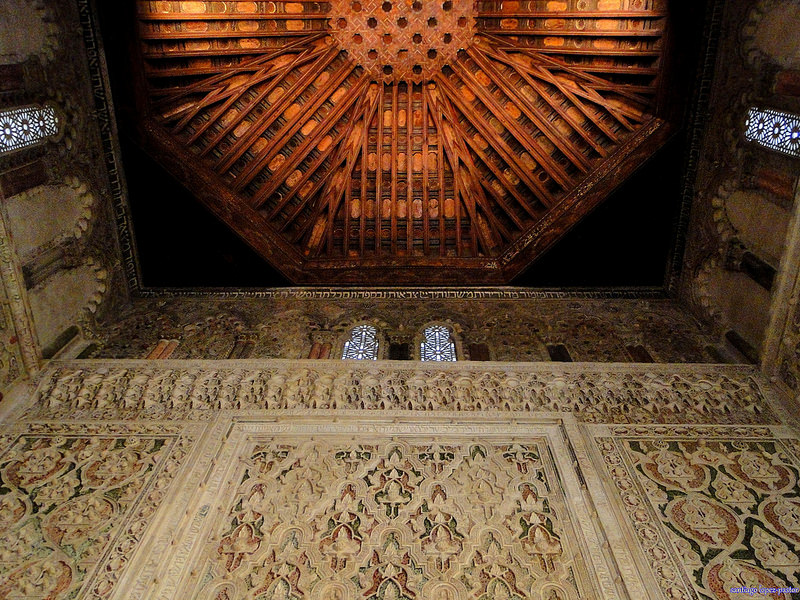

The case of “Holy Toledo” is an extra-special one, given its medieval status as a place where Iberia’s three main religions of the day – Islam, Christianity, and Judaism – coexisted in harmony for centuries. This Castile-La Mancha city was also considered the capital of Sepharad, and dubbed “the Jerusalem of the West”, at its peak home to as many as a dozen synagogues, of which two remain: Yosef ben Shoshan (turned into Santa María la Blanca church, top) and Semuel Ha-Leví (Sinagoga del Tránsito), the latter the only synagogue built in the 14th century, being the notable exception to the prohibition by that time on any new synagogues; right alongside it, the Museo Sefardí de Toledo is a must for understanding the history and culture of Toledan and Iberian Jewry. The Jewish quarter was in the present-day Santo Tomé neighbourhood, including the Puerta del Cambrón. Even today, Sephardic culture remains a part of the city’s fabric, with high-profile annual events such as the European Days of Jewish Culture in early September (this year, on the 6th).

Catalonia/Balearic Islands

Catalonia/Balearic Islands

Honourable mention is due to the calls, the Catalan term for Jewish ghettos. This region’s major cities with major Jewish presence include Palma de Mallorca (where Jews actually at one point reached 15 percent of the total population); Barcelona (where the call was part of the neighbourhood today called the Barri Gótic, the Gothic Quarter); and Girona, where the Força Vella is considered one of the world’s best preserved Jewish quarters. In this last, the star of the Museo de Historia de los Judíos is the collection of tombstones from the Montjuïc Jewish cemetery.

Other Honourable Mentions

The Jewish presence was historically less concentrated in the rest of Spain, but still notable in cities such as Burgos (which had not one but two Jewish ghettos, the Judería de Arriba and the Judería de Abajo), Soria, Valencia, Málaga, and Zaragoza (whose Jewish quarter ended up including five synagogues). Now, more than five centuries hence, arises the chance to build a new, even stronger Sepharad in the land which has over the centuries loomed so large in the history of world Jewry.

images | mosaico.spanishcourses, PHB.cz (Richard Semik), santiagolopezpastor, g.femenias